👋Welcome to the third edition of Starting Early. Every other week, we spotlight new reports, useful news, engaging interviews with people doing important work in the field, and interesting takes on issues that matter.

- We work “upstream” on maternal and infant health and early childhood development — tackling root causes to prevent issuesfrom becoming problems; stopping problems before they become crises.

This week we discuss Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), a term that is relatively new to our mainstream vocabulary and is having a powerful impact on public health discussions and policymaking.

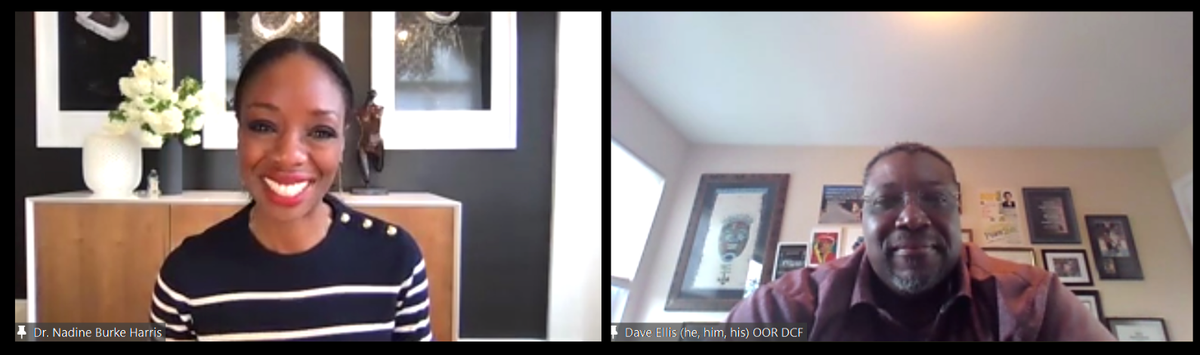

The basic idea is that early trauma and adversity that young children experience can lead to long-term health problems. Dr. Nadine Burke Harris and Dave Ellis — who we interview this week — are doing an extraordinary job connecting the dots.

Please read on and click through the links to go deeper.

Click HERE to view the first two editions of Starting Early.

1 big thing: ACEs Cost the Global Economy $1.3 Trillion a Year

Yes, we said $1.3 trillion a year.💰

The problem: For children, whose brains are still rapidly developing, exposure to highly stressful experiences can result in long-lasting harm.

- These experiences, referred to as Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), are potentially traumatic events that occur at an early age, such as experiencing violence, abuse, or neglect.

- High doses of adversity can lead to toxic stress, which prolongs the “fight or flight” response and floods a child’s body with high levels of the stress hormone cortisol causing changes in brain development, immunity, growth, and attention span.

- ACEs are common and affect 2 out of 3 children in the US. Children growing up with toxic stress may have difficulty forming healthy and stable relationships and can pass on these effects to their own children.

The cost of inaction: Early childhood adversity is among the causes of the top four most costly health conditions: diabetes, cardiovascular disease, cancer, and depression.

- “Our experience taught us an undeniable truth: the massive US healthcare system essentially ignores a root cause of much illness, death, and disability: trauma. It is vital that we all understand what ACEs are and how they impact the burden and manifestation of diseases we commonly see.” — Dr. Arturo Brito, executive director of The Nicholson Foundation, co-founder of the NJ ACEs Collaborative

ACEs need not be our destiny: We can significantly reduce the effects of ACEs and toxic stress by increasing protective factors in children’s lives, such as:

- Fostering strong, responsive relationships between children and their caregivers

- Strengthening the core life skills needed to adapt and thrive

- Reducing the sources of stress in people’s lives

It requires a mindset shift: “We believe these children could live happier, healthier lives if the homes, schools, health care, and mental health systems they grew up in replaced ‘What is wrong with you?’ with ‘What happened to you?’” — Dr. Bruce Perry and Oprah Winfrey in their new book.

2. Dispatches from the Field: Pioneers of Healing and Resilience

Meet Dr. Nadine Burke Harris and Dave Ellis. Each serves in a first-of-its-kind position: Dr. Burke Harris as California’s first Surgeon General and Dave as the first Executive Director of the Office of Resilience in the NJ Department of Children and Families.

On opposite coasts, they champion innovative ways to address and prevent adverse childhood experiences. Dr. Burke Harris shared with us:

“You can’t go and undo ACEs, but you can treat the toxic stress response. We know from research that things like mental health interventions, mindfulness, experiencing nature, and establishing safe, stable, and nurturing relationships and environments help to regulate the biological stress response and improve physical and mental health outcomes.”

We discussed:

- Why they started working on ACEs

- The impact of ACEs in California and New Jersey

- The power of responsive caregiving and a strengths-based responses to stress

“My belief is that the answers sit in community. I understand state government, but like Dr. Burke Harris, I don’t believe the answers are there. I believe the answers sit out with the people who are most directly impacted, who live with this every day.” — Dave Ellis

3. Tackling Maternal Mortality Through Community-Led Solutions

Alarming numbers: In the US, Black pregnant women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than their white counterparts.

New research also connects ACEs and toxic stress exposure in mothers to adverse pregnancy outcomes such as pre-term births and lower birth weight babies and impacts fetal development.

What’s happening: A collaboration of donors, led by Merck for Mothers, launched Safer Childbirth Cities to support community-based organizations in US cities with a high burden of maternal mortality and morbidity. These 20 systems-changing initiatives – from expanding community doula care to improving data systems – directly tackle racial inequities in maternal health outcomes.

“We believe community-led solutions are the most equitable path to strengthen health systems. Local leadership, coordinated action, and women-centered approaches hold the promise to reduce maternal health disparities and improve health outcomes.” – Jacque Caglia, Director of U.S. Programs, Merck for Mothers

Cities paving the way for safer births:

- Austin, TX: The Maternal Health Equity Collaborative is building on their community doulas services to fill a major gap in maternal health by providing child care services to 300 families, including during pregnancy, while giving birth and postpartum, and while accessing vital health services.

- Camden, NJ: Camden Coalition of Healthcare Providers is piloting new models of care by improving citywide data sharing to better link pregnant and postpartum women to earlier prenatal care and critical health and social services.

- Washington, DC: Mamatoto Village and collaborators are strengthening health care for Black birthing people by advocating for high-quality perinatal support services, improving care coordination, and providing new solutions to address homelessness and housing insecurity. Mamatoto created a guide to support Black birthing people during their pregnancy journey.

“By elevating the voices of individuals with lived experiences as part of the Safer Childbirth Cities initiative, we are working to improve the systems that support birthing people of color in the District.” — Aza Nedhari, executive director and co-founder, Mamatoto Village

4. Racing to Address Mental Health Challenges in Schools

What we know: Students are struggling amidst the pandemic. School officials report an increase in students displaying symptoms of anxiety and depression, both of which are exacerbated by the isolation of remote learning.

Furthermore, the pandemic has increased home-based stressors such as food insecurity and housing instability putting children at additional risk for ACEs.

Taking action: In New Jersey, a coalition of partners quickly stepped up to launch a 26-school pilot initiative employing a healing-centered model to address trauma through intensive educator trainings on ACEs, trauma-informed approaches, and mental health. Pilot schools also work with an expert coach to put learnings into practice.

- A healing-centered approach believes that schools can become sites of healing, growth and connection, not sites of trauma or re-traumatization.

- By educating the educators, student-teacher relationships can move towards support and trust-building and away from often-punitive punishments when students act out.

So far, 1,900-plus school staff — from bus drivers to educators — have been trained on ACEs. Each school will develop an action plan to sustain this vital training and help students and staff heal from the pandemic.

On the ground: Zebbie Belton, principal of Carroll Robbins Elementary School in Trenton, NJ, shared that teachers in her school were noticing young children weren’t completing assignments, logging in on time for classes, or turning on their cameras. It was important to understand why.

Because of the new initiative, each school has bridged relationships with community partners. Working with the local PTO and Arm in Arm, the Robbins School is providing families with food, legal services, and even rent money.

Ms. Belton reflected:

“Before the ACEs training, our staff didn’t realize how many layers a lot of children and adults walk around with — as well as how that can affect how we interact with one another. Lots of eyes were opened, and I would say even hearts were opened. Now we can begin to understand why a child is behaving a certain way.”